Shanie Reichman: Include Our Critics or We'll Lose Our Soul

From 'Young Zionist Voices': There are many ways to be a Zionist.

David H.—Delighted to share this essay by Shanie Reichman from Young Zionist Voices. Shanie is the director of IPF Atid, the young-professionals program of the Israel Policy Forum. In this essay, she implores the Jewish world to embrace those young Jews who prefer to connect with Israel through alternative pathways to the political support for Israeli government policy. “It has long been the case,” she writes, “that American Jewish institutions have been unwilling to broaden the Zionist tent enough to address the diversity of Zionist thought and a broad range of perspectives. One’s connection to Israel, however, need not be rooted in support of Israel’s policies or military strategy…”

Global Digital Launch Event: On Tuesday, January 28, Shanie will be joining me, along with other Young Zionist Voices contributors Shabbos Kestenbaum, Adela Cojab, Alissa Bernstein, and Oz Bin Nun, as well as Z3 Project director Rabbi Amitai Fraiman for a moving online conversation about 10/7 and the Jewish future. Click here for info and to sign up!

Shanie Reichman is the director of strategic initiatives and director of IPF Atid at Israel Policy Forum, based in New York City, where she works to elevate the discourse around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and is a frequent host of the Israel Policy Pod. Shanie serves as the founding co-chair for the Forum Dvorah U.S. committee, as a Wexner Field Fellow, a Schusterman ROIer, on the board of Queens College Hillel, on the advisory council for the Center for Ethnic, Racial and Religious Understanding, and as a mentor with Girl Security. Her work has been published in the Forward, the Jerusalem Post, Times of Israel, Hey Alma, Jewish Unpacked, eJewishPhilanthropy, and International Policy Digest.

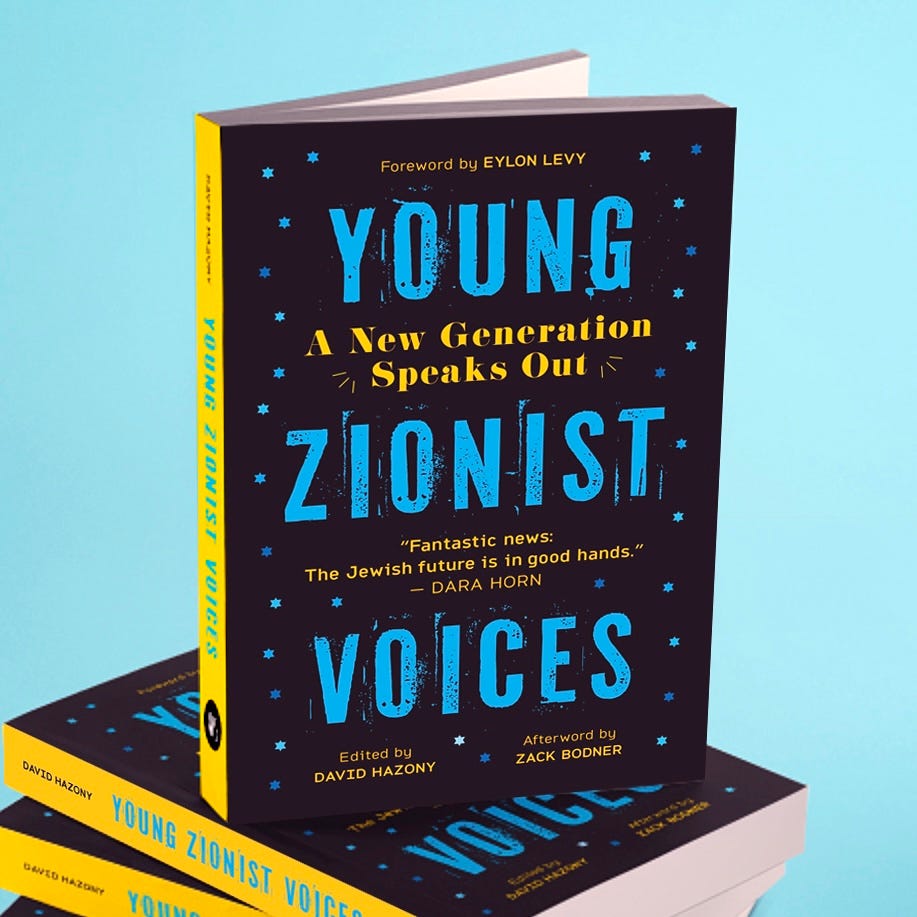

The following is an exclusive reprint from the anthology Young Zionist Voices: A New Generation Speaks Out, edited by David Hazony. Copyright © 2024 Wicked Son. Reprinted with permission.

Include Our Critics or We’ll Lose Our Soul

Make room for young Jews who connect with Israel through culture rather than politics.

Shanie Reichman

“Armchair Zionists living privileged lives in the U.S. have no right to criticize the Israeli government or military while Israelis live in a war zone”—this is a common myth that permeates the American Jewish community. It is reinforced by many Israelis, who view any criticism of Israel abroad as a betrayal of the Zionist cause.

As the director of a young-professional program that embraces individuals with a broad range of pro-Israel views, including those frequently critical of Israeli policies, I often encounter this hurtful rhetoric—and its implicit claim that we, Diaspora Jews, are not sufficiently connected to the Jewish homeland to voice our concerns about Israeli actions.

Such a position not only silences those who are looking to engage with Israel, but also assumes that the destiny of the Jewish state somehow has no impact on that of the Jewish people, wherever they may live. Some Jewish communal leaders not only repeat this rhetoric, but have internalized it in their approach to Israel education, activism, and advocacy.

This comes at a heavy cost. Without setting up a broader tent for our Zionist Jewish community, we risk excluding the many young Jews who feel attached to Israel, but are alienated by some of its illiberal policies. The familiar trope of liberal American Jews “distancing themselves from Israel” is fast becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. Avoiding that will require a profound change in approach from pro-Israel organizations looking to maintain the ever-critical Israel-Diaspora relationship.

***

In IPF Atid, the young-professional network of Israel Policy Forum, we often confront these issues head on: We encourage young adults to dig into the thorniest of issues, challenge themselves and each other, hear divergent perspectives, and use their knowledge to gain confidence in engaging with peers and colleagues who may disagree. Through these discussions emerges a theme of grappling with the starkest generational, religious, and political divides on Israel within the Jewish community, as so many struggle to navigate family WhatsApp chats, Shabbat dinners, and social media posts.

While the political leanings of the American Jewish community are stable across age groups, the older generations’ long memory of an Israel that was both the underdog and represented by left-wing leaders, many of whom actively pursued peace, makes them resilient in the face of a changing Israel. Their connection will never be at risk so long as they can view Israel within the arc of history instead of focusing on the past decade.

I, however, was born two months before the November 1995 assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. I have little memory of an Israeli prime minister who wasn’t from the center-right, and since I’ve followed current events it has almost always been Benjamin Netanyahu. The Israel of the Kibbutzim, of Golda Meir and Rabin, is long gone.

And while mourning those losses can be important, it’s more productive to grapple with the current reality in a way that preserves the crucial relationship between American Jews and Israel. My generation and those younger than me struggle to associate Israel with many of the values that permeate American Jewry’s dominant culture and institutions. Many of us find ourselves expressing concerns with Israeli policy, only to be confronted with reminders of wars fought long before we were born. Understanding and internalizing the history of the Land and State of Israel should not come at the expense of developing a mature and critical voice, when it comes to its present and future.

Attempting to differentiate the State and people of Israel from their democratically elected leaders is challenging, but can be overcome with the right framing. Fortunately, there are ample opportunities for our vibrant community to accommodate multiple views and to reignite a passion for engaging with Israel, beyond those in the traditional hasbara space.

***

It may seem obvious to some of us that since Israel is the homeland of the Jewish people, each and every one of us has both a right and even an obligation to be invested in its future. Over the last two and a half decades, the Jewish community has invested billions of dollars in strengthening the connection between young American Jews and the State and people of Israel. This cause is both noble and deeply vital, forming a cornerstone of our collective future. We can embrace the ideal that whatever its politics, the Diaspora can and should maintain a connection to Israel and identify with Zionism.

However, this critical relationship is now under threat, challenged by an Israeli government comprising far-right, ultra-Orthodox, and anti-pluralistic politicians. As we grapple with the disconnect between Israel’s government and the 70 percent of American Jews who are liberal, there is a reluctance to rethink our approach and innovate in the way we build pro-Israel communities.

This leaves little room for common ground with liberal young American Jews, many of whom shy away from even talking about Israel today. Over the course of the Israel-Hamas war, many liberal and progressive young American Jews have felt deeply isolated as they navigate painful conversations and experience hate from the very peers, colleagues, and fellow activists they may have worked alongside for years, many of whom turned against the Jewish people as early as the day of October 7. Some of these young Jews had not been engaging with Israel at all prior to the war, but were so shocked and alienated by their progressive communities that they were compelled to seek out Jewish community in the midst of the crisis.

This tension between a right-wing Israel and a left-wing American Jewish population has been brewing for almost half a century. It has long been the case that American Jewish institutions have been unwilling to broaden the Zionist tent enough to address the diversity of Zionist thought and a broad range of perspectives. One’s connection to Israel, however, need not be rooted in support of Israel’s policies or military strategy, though that is how we most often see it manifest. There are countless paths to engaging deeply with Israel, including culture, language, activism, and policy (my personal favorite).

To be sure, before October 7, pro-Israel Jewish organizations had gradually begun to tolerate increasingly divergent opinions on Israel, particularly in the wake of the November 2022 election of Israel’s most right-wing government in history and the anti-judicial-reform protests of the following year. That said, since the Simchat Torah Massacre, and in an effort to develop a unified voice, we’ve begun to fall in line. We have come to fear any dissent regarding Israel’s actions, both political and military. While there is a temptation to be cautious about criticizing Israel in the middle of a war and amid the sea of antisemitic and anti-Israel discourse across the country, a nuanced approach that allows for measured and thoughtful questioning and critique would provide an outlet to those who disengage for fear of reproach, and avoid a potential backlash from those feeling silenced.

Today we are presented with a unique opportunity, as surveys show a “surge” in overall Jewish engagement in America since October 7. By embracing a broader vision of Zionism, our community can ensure inclusion and shared definitions that lead to a sense of belonging within the pro-Israel community.

A recent survey by the Jewish Federations of North America revealed a stunning fact: While 90 percent of American Jews believe Israel has a right to exist as a Jewish state, and 91 percent support Israel over Hamas in the current war, only 46 percent identify as Zionist—with another 32 percent saying they “don’t know” whether they are Zionist, as well as 17 percent who call themselves “non-Zionist” (only 5 percent identify as “anti-Zionist”).

It is safe to assume that those who support Israel’s right to exist, but don’t know whether they are Zionist, come mainly from the liberal flank of the community (though some are likely from the Ultra-Orthodox community)—as do many who say they are “non-Zionist.” This provides an opportunity to promote a more complex interpretation of Zionism that can lead to most of the 90 percent of American Jews who embrace Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state to identify as Zionists. My preferred definition is “support for a secure, Jewish, democratic state of Israel.” Surely more than 46 percent of American Jews would support this.

A wider definition of Zionism would be, in many ways, a return to what once was. The Zionism of my grandfather’s generation was centered around one goal: the establishment of a flourishing Jewish state. My grandfather’s Zionism expressed itself through his learning the Hebrew language, smuggling Iraqi Jewish refugees into Mandatory Palestine in the wake of the farhud pogrom, raising an Israeli flag atop his synagogue in Tehran, and ultimately moving to Israel to fight in the newly created IDF. Certainly his story is an extreme example, but he coexisted, mostly peacefully, with religious Zionists, cultural Zionists, labor Zionists, and others who did not subscribe to an identical worldview of what Israel should look like, at a time when the stakes were arguably higher than they are today.

My Sabba, who ended up aligning with the Revisionist Zionism movement founded by Vladimir Jabotinsky (the forerunner of today’s Likud), might have choice words for other approaches to settling the Land of Israel—but to him there was no question that we were all one community. The understanding of all the Jewish people being part of the Zionist project in its many forms will support our ability to make space in the tent for those who demand openness to questions about the current reality.

***

There still remains the question of how to put this broader-tent strategy into practice. One path will require the inclusion of Palestinian perspectives in our community’s approach to education and dialogue. This cannot be achieved through tokenizing the few Palestinians with whom we entirely agree or who identify as pro-Israel, but rather platforming voices that make us uncomfortable. Nationwide, 81 percent of American Jews feel empathy for Palestinians (a mere 1 percent lower than the rate for non-Jewish Americans), so this should not be perceived as controversial by large swaths of the community.

Another crucial component of including the liberal camp in the Zionist discourse is building connections between Israeli and American Jews who share the values of equality, democracy, and pluralism. This solidarity movement will address a growing American-Jewish perception that Israelis are exclusively represented by their hawkish and even far-right leadership. The protest movements in Israel have done a tremendous amount to fight back against this narrative and to showcase the resilience of Israeli society and the distinction between the government and its people. If young liberal American Jews can seek out, collaborate, and build relationships with Israelis who share their values, it will highlight the contrast between Israel’s government and its people—a necessary task after over a decade of Israeli leaders for whom most American Jews would never vote.

Change is always risky, particularly for a minority community like ours. And yet, we have more to lose by risking the credibility of Zionism, if it cannot contain the divergent views of many pro-Israel Jews, and even alienates those who should fit neatly into the movement but have been left out. I am heartened by my work with incredible partners at American Jewish organizations around the country who are similarly concerned with recent trends and committed to advancing a nuanced approach to Zionism and Israel programming. This leaves me hopeful that there is a growing commitment to elevating the discourse and broadening the scope of our work when it comes to Israel.

The Jewish community is generally exceptional at embracing diversity of thought on religion, philosophy, and a range of other topics. We continue the legacy of Israel’s founding leaders who embodied vision and courage. Should we choose to carry the torch of those who risked their lives in the name of Jewish peoplehood and sovereignty, we will surely see a more resilient and durable Zionism, one that fulfills our obligations to the next generation of Jews around the world.

I think that it can be universally agreed that Zionism from inception until 1948 was a movement to support a Jewish homeland (Israel). After 1948, I believe, Zionism represented the continual existence of Israel as the Jewish homeland. Did I miss something? Zionism appears to be a relatively simple concept. Does being a Zionist also include include the right to dictate how that nation chooses to conduct its affairs? I think not. The citizens of Israel should have the only voice. Not people living elsewhere that might become Israeli citizens at some future time. Do the non-citizens have the right to voice their opinions? If you live in US, that's affirmative. But, to insist one has the right to dictate to Israel, especially where its security is concerned, just about rules out your right to call yourself a Zionist. To insist, sitting in the US, that Israel make peace, accept a cease fire, give up land that is rightfully theirs, you are no Zionist, or even a friend. When you are a nation with an enemy whose purpose is to totally annihilate you, your only counsel should be your own citizens and those that support your policies.