Noah Shufutinsky: Zion, Our Spiritual Lifeline

From 'Young Zionist Voices': Stop apologizing and start living the ancient dream.

David H.—After last month’s amazing launch of Young Zionist Voices, I’m proud and excited to begin sharing some of its essays, beginning with Noah Shufutinsky’s “Zion, Our Spiritual Lifeline.” I’ve been delighted to get to know Noah through this process—through his teaching, his art, and his writing, he has shown himself to be built of the stuff that will carry the Jewish people forward in the coming generation.

Noah Shufutinsky is a Jewish educator, lecturer, and musician based in Bat Yam, Israel. He earned his B.A. in Judaic Studies at the George Washington University, where he was heavily involved in Jewish life and Zionist activism. Noah is also known by his stage name, Westside Gravy. As an artist he fuses his passion for Jewish culture and history with his lived experience of growing up Black and Jewish across the United States, to write and produce hip hop. As an educator with StandWithUs, he speaks about topics regarding Israeli and Jewish history, connection to the homeland, and how antisemitism affects Jewish people around the world.

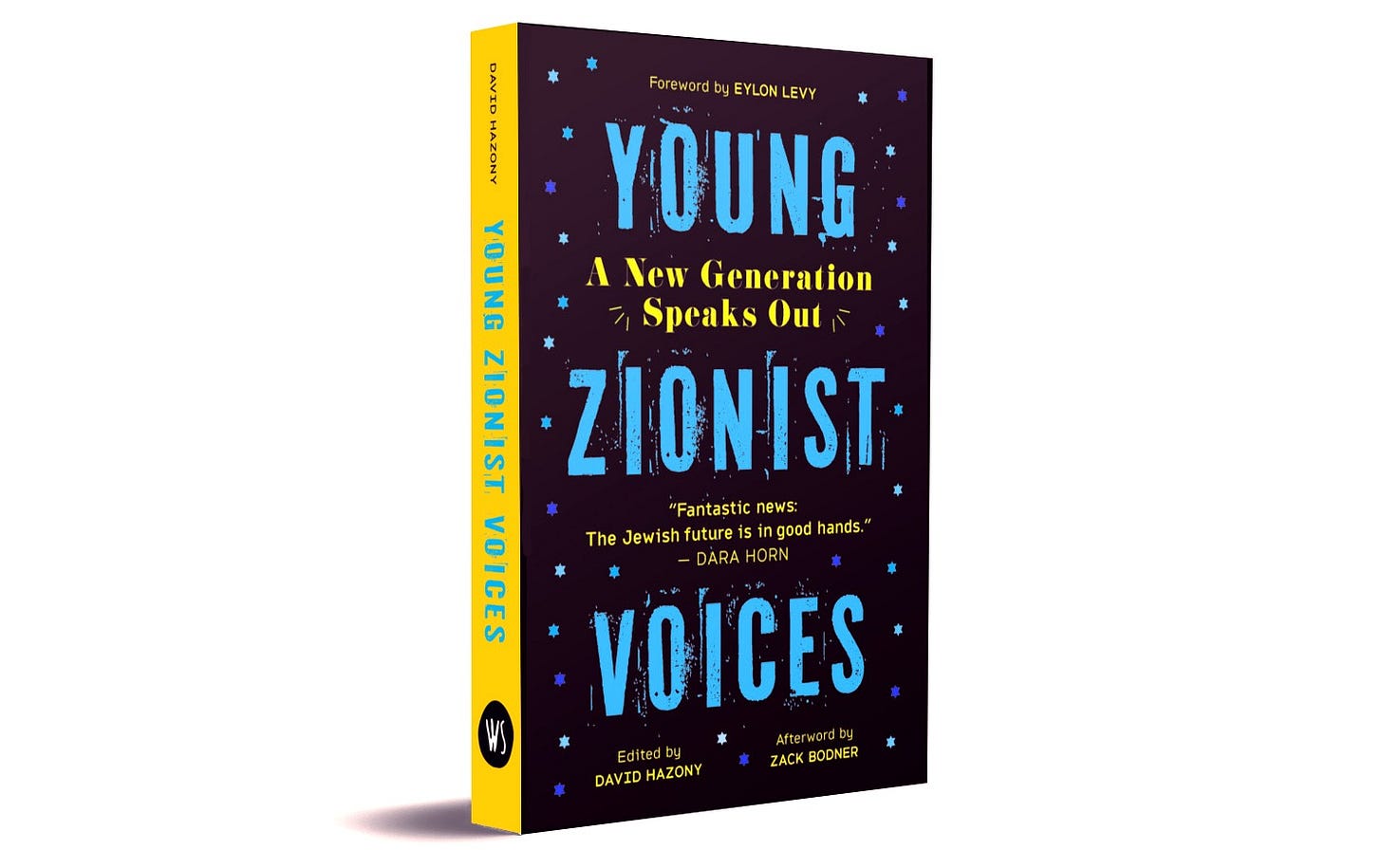

The following is an exclusive reprint from the anthology Young Zionist Voices: A New Generation Speaks Out, edited by David Hazony. Copyright © 2024 Wicked Son. Reprinted with permission.

Zion, Our Spiritual Lifeline

A new book captures the rise of a generation of Jews who have chosen the path of pride.

Noah Shufutinsky

I’ll be honest. The question of why I am a Zionist is something I never asked myself, neither before nor after I heard it used as a slur. Not before I knew how many times the word “Zion” appeared in our holy texts. Not after I set foot on the slippery Jerusalem stones that harnessed the cold winter air of January 2018.

That was the first time I’d visited Israel. Growing up, I understood the importance of the land, and I felt the connection to it from thousands of miles away. But it wasn’t until a month and a half after turning eighteen that I had the chance to visit for the first time.

In the back of my mind, I had a lot of questions about what it would be like. Would it live up to my spiritual expectations, or fulfill my longing to feel at home the way it had for my older brother on his first trip? One thing I knew for sure was that generations before me had struggled to maintain and to pave the way for my own Jewish identity, and I was on my way to the center of the Jewish past.

What I didn’t realize was that I was also on my way to the center of the Jewish future, collectively and personally. I was on the way to my future home, which is a weird thing to comprehend.

***

I grew up as a Navy brat, moving around every three years. Home for me always meant wherever I was temporarily living, as long as my family was there. But in the back of my mind I also understood that Israel was home, because it was the home of my ancestors and the shared home of my brothers and sisters. It was a strange feeling to be heading home for the first time at eighteen, not just viewing the land in a spiritual way, but as a physical place where my feet would step, my voice would echo, my nose would smell, and my eyes would see.

As a people, historically, that is where we come from. It’s the genesis of the blood that courses through most of our veins and the determination that beats in all of our hearts. It’s the birthplace of the synonymous syllables that exit our mouths in a variety of accents. It’s the place that, regardless of how long we’d been dispersed or what conditions we’d experienced, we vowed to return to. The basis of Zionism is that integral part of our identity that has been present in every single generation in every single Diaspora community. The longing, and action, to make a return home feasible.

Religiously, we hold the land tight in every aspect of our lives. Whether it is the direction we pray, the place where our dietary laws originate, or the plants we wave around a few days a year—just like the roots of those plants, our practices are indigenous to that ground.

But I didn’t grow up with every aspect of that religious life. Like many other children of various backgrounds, my experience as the son of a Soviet Jewish refugee meant that even without those practices, my connection was equally deep.

We often hear stories of how Israel was a physical lifeline for Jews of Europe as well as of the Middle East and North Africa. The only safe haven for persecuted minorities. I want to tell a different story. I want to tell you how Zion was not just the physical lifeline, but also a spiritual lifeline.

Long before migration back to our homeland was possible, the parents and grandparents of those Mizrahi, Sephardi, and Ashkenazi refugees of the twentieth century relied on their return, their Zionism, to survive in community with one another. Zion, no matter the distance it was, helped ingather the exiles while they were still in exile.

But this isn’t just a pre-twentieth century story. For my dad and families like his, who were born in a country where the regime had outlawed all Jewish practices on a basis of anti-nationalism, they in turn recognized Jewish national identity. In a world without Hebrew, Jewish holidays, kosher restaurants, thriving synagogues, and all the other benefits of Jewish life I enjoyed as a child in the United States, the thing that kept them connected to their roots was the mere knowledge that they were from Israel and would someday return.

That was in 1981. Fast forward thirty-seven years, and I was in the midst of that return. So the question of why I am a Zionist isn’t something I could ever fathom asking; it’s something ingrained in the story of every Jew born into our tribes and every Jew who spiritually returns to our ranks by adopting the practices of our nation. It’s the homecoming I had at eighteen, that I unknowingly longed for.

***

While I have never looked for a cut-and-dry answer to that question, I have been forced to find an answer for people unfamiliar with that story. The story they are familiar with isn’t one of an indigenous people returning to their brothers and sisters in the land they were born of. It’s a false narrative of white-European-settler-colonialism that my very existence interferes with. Nevertheless, this narrative has penetrated all aspects of society, from college professors in lecture halls like the ones I sat in not too long ago to entertainment awards shows, from newsrooms to Instagram stories of everyone’s favorite musician—or a washed-up one with a decades-old hit about finding cheap clothing.

This challenge has required me not just to find my answer as to why I am a Zionist, but to find the specific quality necessary to convey my answer. What is required is a healthy dose of unapologeticism, which is sometimes viewed as unhealthy in today’s world. But unapologeticism begets respect. In a world where everything has to have a grey area, we often try to find it even in the black-and-white. It’s a good thing to look for dialogue and nuance, but certain things are not up for debate.

So when I take a trip down memory lane, which isn’t that long of a road for someone of my age, I think back to my first few days on campus. My peers who heard that I’m Jewish immediately questioned me regarding my opinions on Zionism and Israel. And I went out of my comfort zone and what I knew in my heart, to present a very neutral perspective on the area—explaining that I loved my homeland but also had disagreements with its policies.

For far too long, that is the answer Jews in my generation have been trained to give: one of reaction rather than action, an answer of being poised to apologize for an accusation not yet leveled. We want friends, we want to sound reasonable, and we look for concessions we can make to those who despise us.

My answer today, however, is much simpler. It is thoroughly unapologetic. It was upon walking the streets in Israel that I realized the results of these concessions and the grave danger of compromising on the central fact that Israel is our home. The stories I’d learned about refugees having nowhere to go except home became real and human. The soldiers who had lost friends for the sake of our homeland did not put their lives on the line out of concessions. They did so out of pure love and commitment to our nation that originates in this land, as well as the idea that affirms our right to live as a free people here.

This commitment sometimes gives way to compromise. I met Israelis who believed in a two-state solution, one-state solution, and everything in between. Some agreed with my positions, some disagreed, but the basis of their opinions was not based in concessions. This same approach has to be adopted in the Diaspora on the ideological battlefield.

That shaped my answer into what it is today. Israel is my home. It’s where my people are from and where we have succeeded in returning to. It’s where I am rarely questioned regarding my appearance as a Black Jew, and where my identity is not tokenized for a political point. It’s the land that gives me the inspiration I need to make freedom songs—not those longing for liberation or lamenting a loss of it, but songs representing what a free Jew looks and sounds like. Whether it’s a love song in Hebrew, a political manifesto in musical form, or even just instrumentation playing melodies that have developed in this land over thousands of years, and today remind listeners of the origins of our prayers—this is the sound of freedom. The sound of a Jew unchained and able to express himself fully, rather than having his identity confined to a reaction to a false narrative. A Jew whose voice resonates within the walls of his home and flows out of open windows beyond the surrounding city, into the countryside.

Our Zionism isn’t a reaction to bigotry or policies. It’s the story of who we are, beginning with where we are from, documenting how we got to everywhere we’ve been, and ending with where we will always be. Home.

Very nicely expressed and written. Being Jewish can often be a tough road to travel. I can only imagine how bumpy that road is for a Jewish Black. As a Jew aware of your history, your roots must always be firm and deeply grown. There can be no reason to compromise or apologize. Our history is ours only, and must be learned and respected. There can be only truth, revealed by the wisdom of the ages. You cannot please or appease. What is right is right, and anything that drifts is wrong. Jews must always be Zionists-- apologies not accepted. If you live as a moral, ethical, spiritual Jew (a little religion doesn't hurt) you will be respected and accepted.